|

Willia Easter Haywood

|

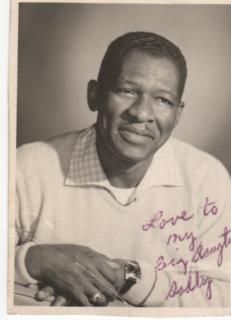

First of all, she had the brightest smile and looks just like my mother. Mom said that her personality was similar to Auntie Amina's. I really wish I could have known my maternal grandmother. Mom said Willia Easter loved to dance and have company over to the house. She was friends with recording artist Lloyd Glenn and his family, who were also from San Antonio and would come by the house on 127th and Central. He, his wife and kids would come over. Lloyd played the Haywood piano for Willia and neighbors would come by to sing and dance. Oh, and she hated California. Mom said it was because all of Willia's family was in San Antonio, Texas. I wonder now if Willia Easter had a premonition about her bleak future in California. Did she ever think she was going to “pass away” at 29 years old, just two weeks shy of her 30th birthday and leave her husband and two daughters behind? Is that why she hated California?

My mom described her mother’s death as passing away. However, in 2003 her distinctive sweet smelling cedar chest, which is the scent of home to me; it's mom opening up joys and wounds from her past. It's where she keeps the handmade dress that I was christened in. Mom's prom dress from high school, our school drawing and Christmas cards. A time capsule of her life neatly folded between photo albums, dance cards and press floral corsages. It's where I found the funeral book and newspaper clipping from the LA Sentinel, June 1948, "Two women held to answer for murder charges." Now, I am confused because I thought there was one woman that hurt my grandmother. Turns out the title was about two different women, but my grandfather only clipped the story about his wife. Now, I want to, I need to know more. That was 2003 and we (Constance Joyce Haywood Shepherd Thorns and I) are finally having that conversation in 2020, when Mom has travelled 82 times around the sun.

Mom started talking more about what happened to Willia Easter when I was an adult. My grandmother was named after her Aunt Easter (yes, Easter like the resurrection of Christ -- but not Willie or "Willie-uh," more like Will-ah Easter).

The story about the death of Willia Easter was commingled with the arrest of two women for two different murder charges. As jarring as this article is to read, I really wondered now what it was like mentally for the children Willia left behind.

There was no therapy for Black families back then that suffered trauma. If your family was ever enslaved your entire life was traumatic and the warped views of corporal punishment were passed to each generation. In 1942, European immigrants who served in the US armed forced were offered an opportunity to become US citizens and given a chance to acquire land and loans. However, African American citizens did not find these types of prospects very easily because of the Black Code and Jim Crow laws. Hence, therapy was not a top priority for many people at that time of any ethnicity trying to stay off the streets.

You could have been 10 years old, worrying about how to multiply in Ms. Gorman’s 4th grade class at Willowbrook Elementary School. However in the middle of the day, Mr. Driver, your dad’s best friend, could have come to pick you up from school, in the middle of the day to take you home and no one tell you why.

You could have been 10 years old and anxious to get home because your knees were not scuffed and your dress wasn't torn and your hair was still neat, just like mommy likes it. Especially since the day before you and your mother had a "discussion" about your tomboy ways; your scuffed up knees, again. Your hair all over your head, again. And, your dress was probably torn at the waist, again, from playing pop the whip. The night prior for mom and Willia was contentious.

On the ride home with Mr. Driver, who isn’t saying anything, you could have been thinking, “Did I clean the bathroom good this morning before I left the house?” It was a daily routine to get up in the morning and do chores before leaving the Haywood house. Your 10 year old mind could not have imagined that someone was going to tell you, you are not going to see your mother anymore.

There was no therapeutic protocol for what to do with a little 10 year old Black girl and her 4 year old sister who just witnessed her mother being stabbed in the jugular vein in the front yard of the house, a place where they would play hide-and-seek.

There was no therapeutic protocol for what to do with a little 10 year old Black girl and her 4 year old sister who just witnessed her mother being stabbed in the jugular vein in the front yard of the house, a place where they would play hide-and-seek.

There was no therapy for a Black man who worked two, sometimes three jobs, because he wanted to make sure his wife could be home for the children and not have to work. There was a certain honor in that for Robert Lee Haywood, my gramps. There was, however, the normal protocol of let’s not talk about it because Dad has to get back to his jobs before someone else who also has a family to feed takes his place.

There was the typical protocol of we'll just whip the little four year old girl and eventually she’ll pull it together. It should be expected that after decades of not talking about it that the little girl grows up to be a woman who blames herself for not doing more to save her mommy and that the little girl would grow up to change her name from Frances to Amina and might try to kill herself at least two times. "They weren't quite sure what to do with her," my mom said.

Apparently, my Aunt May was pretty good at trying to help Frances. Aunt May was independent and smart. “She was the only woman I knew that owned her own hair salon," my mom Connie explained. "Not just the business, but the land and the building in San Pedro. She also owned the apartment building along with the business and the house behind it.” Aunt May saved her money back then and when the opportunity availed itself, she had the cash. No need to go to the bank for a loan, who would surely deny her access to wealth, anyway.

Therapy back then was an "insane asylum" or let’s just get back to normal as soon as possible.

Therapy back then was an "insane asylum" or let’s just get back to normal as soon as possible.

But Willia Easter loved to dance. She loved having company over to the house. She doted over her children, her house and her husband.

“We didn’t really talk to dad much before mom passed away,” Constance "Connie" Joyce Haywood Shepherd Thorns, my mother told me. “He was always working so hard. He would play with us a little when he got home, cuddle with mom, eat dinner and go to bed to start work all over again. [After her death] He was not the same man that you knew."

Gramps, that’s what we grandkids called Robert Lee Haywood, held many jobs. When I knew him, he was a man of leisure. A landlord of multiple properties and an avid golfer. On the golf course, and among so many other family and friends, he was Uncle Bob. My mom said her dad was much different from the Gramps I knew. Back in 1948, 30-year-old Robert Lee took the death of 29-year-old Willia Easter the hardest. But the support system came to his aid. Aunt May stayed with the family for three to five days, until Sarah "Mama Sadie" Haywood arrived from San Antonio to be with her grieving son and her traumatized grand daughters. Her stay lasted for six years. That was a form of therapy for the family.

Gramps, that’s what we grandkids called Robert Lee Haywood, held many jobs. When I knew him, he was a man of leisure. A landlord of multiple properties and an avid golfer. On the golf course, and among so many other family and friends, he was Uncle Bob. My mom said her dad was much different from the Gramps I knew. Back in 1948, 30-year-old Robert Lee took the death of 29-year-old Willia Easter the hardest. But the support system came to his aid. Aunt May stayed with the family for three to five days, until Sarah "Mama Sadie" Haywood arrived from San Antonio to be with her grieving son and her traumatized grand daughters. Her stay lasted for six years. That was a form of therapy for the family.

Robert Lee worked very hard to take care of the family and now his world was turned upside down. Willia Easter was the one who took care of the household, used his money to pay the bills and she was the one that raised the girls and saw about their schooling.

Willia Easter was feisty, too. Mom said that when they first moved to San Pedro from San Antonio Texas in 1944, Willia was arguing with the school about why her daughter had to be held back a grade. “She already learned that stuff in Texas, why does she have to take it again in California?”

My mom, Connie, was six years old when Gramps sent for the family to join him in California. Auntie Amina (aka Frances) was just born, it was 1944. Connie was the first grandchild on either side of the family. “I felt like a princess in Texas, and now, in California I had to learn how to fight.”

One day, Connie came home singing a song she heard in school several times, “Eeny, meeny, miney, moe, catch a nickel by the toe.” She was one of maybe two Black children at the school.

“Have you ever heard of a nickel having a toe?” Willia Easter asked her six-year-old daughter.

“No”

“Well, what do you think that means?”

“I don’t know. I heard them singing it at school.”

“Uh-huh. It's not nice and someone is being mean.”

Well the next day, Willia Easter marched up to that school in San Pedro sometime between 1944-1945 and gave that school a piece of her mind. “I don’t know what she said,” Connie recalled,” but no one ever sang that song around me again. That was the first time I had anyone ever call me the N-word. No one ever called me that in Texas, my family never said it and I really did think they were saying ‘nickel.’”

That was one of the many times Willia Easter went up to the school to protect her daughter. Another time was when Willia asked her daughter how was school today and Connie answered, “I couldn’t see what the teacher was talking about because I kept getting pushed to the back.”

Well, after Willia Easter went up to the school that time Connie was no longer pushed to the back. Mom said that Willia Easter was always laughing and dancing, but that she was also sad. Willia told mom that she had to learn how to fight because if Connie didn’t she was going to get a whoopin’ when she got home.

So when the family moved around 1946 from San Pedro to 127th and Central Avenue, Connie quickly made friends and when a boy slapped a sandwich out of her hands, she would fight him, because Willia Easter words rang in her ears, ". . . or you'll have to fight me." If they pulled her hair, she would fight those boys. Not at first of course this happened over time. Mom went from being the little princess to the little tom boy.

She’s still friends with many of the kids that were in her fourth grade class with Ms. Gorman at Willowbrook Elementary School. They culminated together to Willowbrook Junior High and then graduated from Centennial High School, class of 1956. In 2006, they celebrated their 50th Class reunion.

|

Their last family picture together (Willia Easter, Connie, Robert Lee and Frances [aka Amina])

|

There was no therapy for Connie’s little friends, either, who knew that something bad had happened to Connie’s mom. One of mom's friends said they felt so bad when Connie had to leave school because, "you didn’t know why you were leaving early [that day], but the teacher told us and we were so sad for you.”

So, after a traumatic experience and the collective community says let’s get back to normal, because we have to survive, grieving is a luxury. I think of what that must mean when your normal is interrupted? Willia Easter wasn't coming back anymore, there would be no more normal as Connie and Frances knew. There would be a lifetime of suppressing the pain, putting on smiley faces and figuring it out for themselves so they can survive. There was also the strength of moving forward, not dwelling in the sadness. Today that has manifested in my mom having a real problem with knives being displayed on the kitchen counter. I did not not realize until in 2003, when I found that article written in 1948 from the LA Sentinel about how Willia Easter passed away, that mom's phobia about knives may be rooted in that incident.

Families. My siblings and I had the best childhood ever. Our parents made us believe that true happiness starts with being happy with who you are. And that grounding, my dad said, comes from knowing who you are and from whence you came. They taught us to put God first, stick up for ourselves and for justice. My mom and dad also taught us to learn about other people, all kinds of people, before passing judgement. And, did we have a good time with our cousins? Yes, we still do. I know that's because mom and dad each have wonderful memories of time with their own cousins.

I am so grateful for Grandmother Lurena Haywood who married Gramps many years later and was by his side for decades until his death in 1992. Lurena taught us so much about the Haywood family because she was always mentioning people she said we should know. Lurena, who passed away in her 90's in 2016, was the grandmother God gave me and I love her dearly.

But every time I heard about Willia Easter I would wonder, what was she like? When I look at the few pictures I can find of her, I see glimpses of Connie and Amina. I wonder what it could have been like to be at one of her parties to watch Willia Easter dance and entertain. That’s what my mother said she remembers most about her own mom. Willia Easter loved to dance and had a good time before she left this earth.

VIDEO

Here's a 46-minute video of my mom talking about her mom, Willia Easter Haywood. I learned so much about how my grandmother lived and how the way she died affected my mom, my auntie and my grandfather. The music in the video is from my grandmother's hometown friend Lloyd Glenn. She would have been dancing to a song like this.

References

Anacker, Karen B. “Death of a Suburban Dream: Race and Schools in Compton, California.” Journal of the American Planning Association, by Emily Straus, vol. 81, no. 1, 2015, p. 78., doi:10.1080/01944363.2015.1030935.

Glenn, Lloyd Colquit. “Chica-Boo.” Discogs, Aladdin Records, 1956, www.discogs.com/Lloyd-Glenn-Chica-Boo/master/1056029. Real name - Lloyd Colquit Glenn - American jazz and blues pianist.

He worked with : T-Bone Walker, B.B. King, Kid Ory, Big Joe Turner, Lowell Fulson (& others) and with his own groups.

Google Maps: 1118 E. 127th Street, Compton, Google, Apr. 2017, www.google.com/maps/@33.9177765,-118.2551317,3a,75y,239.18h,92.62t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sv0DDgze2CJsm4C7xyn4yqg!2e0!7i13312!8i6656.

History.com Editors. “The Great Migration.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 4 Mar. 2010, www.history.com/topics/black-history/great-migration.

“L&L Kilns Easy-Fire EFL 2026 Front Loading Kiln: Sheffield Pottery Kilns.” Sheffield Pottery Inc., 2020, www.sheffield-pottery.com/L-L-Kilns-Easy-Fire-eFL2026-Front-Loading-Kiln-p/lkefl2026.htm.

Mawdsley, Dean L. Steel Ships and Iron Pipe: Western Pipe and Steel Company of California. Associates of the National Maritime Museum Library, 2002.

“Military Naturalization During WWII.” USCIS, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 23 Sept. 2013, www.uscis.gov/history-and-genealogy/our-history/overview-ins-history/military-naturalization-during-wwii. Last reviewed 12/09/2019

Moigne, Yohann Le. “Emily E. Straus 2014: Death of a Suburban Dream: Race and Schools in Compton, California. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 21 July 2016, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1468-2427.12326.

“Princess Crown 1 Vinyl Decal Sticker.” IRockDecals, 2020, irockdecals.com/princess-crown-1-vinyl-decal-sticker/.

Srivastava, Jyoti. “Navy Pier: [Crack the Whip - by J.Seward Johnson Jr.].” Chicago Outdoor Public Art - Crack the Whip by J. Seward Johnson Jr., 15 Sept. 2010, chicago-outdoor-sculptures.blogspot.com/2007/11/eight-kids-navy-pier.html. Used with written permission (via email) on July 13, 2020

“Two Women Held to Answer for Murder Charges.” Los Angeles Sentinel Newspaper, June 1948.

“Victory Garden.” Wikipedia: Victory Garden, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 July 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victory_garden#/media/File:Victory-garden.jpg.

“Water and Power Associates Informing the Public about Critical Water and Energy Issues Facing Los Angeles and California.” Water and Power Associates, Water and Power Associates, 1952, waterandpower.org/museum/Early_Views_of_the_San_Fernando_Valley_Page_4.html. A Los Angeles-bound Pacific Electric Railway car on Sherman Way. The line ran from North Hollywood through Universal City to the Subway Terminal Building in downtown Los Angeles.*